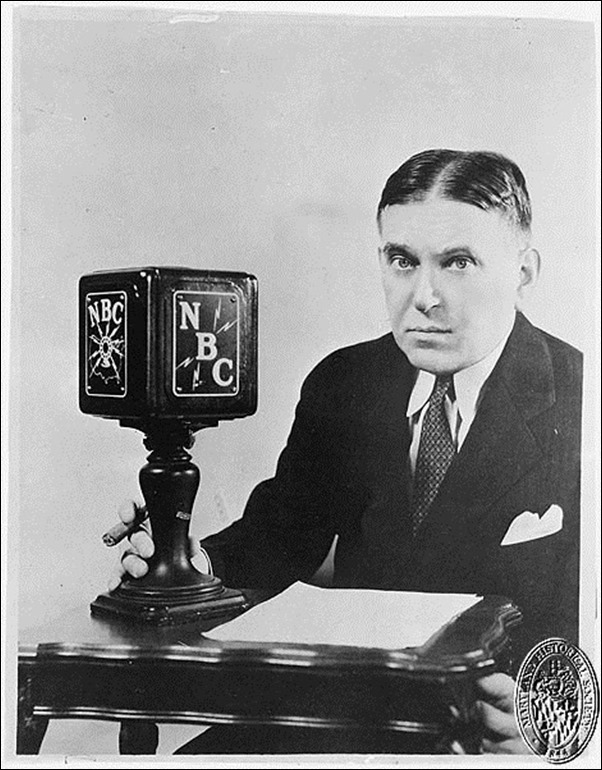

As today’s the birthday of the Sage of Baltimore, optimism becomes an increasingly alien concept for me, and I saw a passing mention to this piece in Michael Rose’s Infernalia (which I plan to review in the next week or two), enjoy Mencken’s meditations on the absurdity of hope.

~MRDA~

The Cult of Hope

by H.L. Mencken

From Prejudices: Second Series, 1920, pp. 211-218

Of all the sentimental errors that reign and rage in this incomparable Republic, the worst is that which confuses the function of criticism, whether aesthetic, political or social, with the function of reform. Almost invariably it takes the form of a protest: “The fellow condemns without offering anything better. Why tear down without building up?” So snivel the sweet ones: so wags the national tongue. The messianic delusion becomes a sort of universal murrain. It is impossible to get an audience for an idea that is not “constructive”—i.e., that is not glib, and uplifting, and full of hope, and hence capable of tickling the emotions by leaping the intermediate barrier of intelligence.

In this protest and demand, of course, there is nothing but the babbling of men who mistake their feelings for thoughts. The truth is that criticism, if it were confined to the proposing of alternative schemes, would quickly cease to have any force or utility at all, for in the overwhelming majority of instances no alternative scheme of any intelligibility is imaginable, and the whole object of the critical process is to demonstrate it. The poet, if the victim is a poet, is simply one as bare of gifts as a herring is of fur: no conceivable suggestion will ever make him write actual poetry. And the plan of reform, in politics, sociology or what not, is simply beyond the pale of reason; no change in it or improvement of it will ever make it achieve the impossible. Here, precisely, is what is the matter with most of the notions that go floating about the country, particularly in the field of governmental reform. The trouble with them is not only that they won’t and don’t work; the trouble with them, more importantly, is that the thing they propose to accomplish is intrinsically, or at all events most probably, beyond accomplishment. That is to say, the problem they are ostensibly designed to solve is a problem that is insoluble. To tackle them with a proof of that insolubility, or even with a colorable argument of it, is sound criticism; to tackle them with another solution that is quite as bad, or even worse, is to pick the pocket of one knocked down by an automobile.

Unluckily, it is difficult for the American mind to grasp the concept of insolubility. Thousands of poor dolts keep on trying to square the circle; other thousands keep pegging away at perpetual motion. The number of persons so afflicted is far greater than the records of the Patent Office show, for beyond the circle of frankly insane enterprise there lie circles of more and more plausible enterprise, and finally we come to a circle which embraces the great majority of human beings. These are the optimists and chronic hopers of the world, the believers in men, ideas and things. It is the settled habit of such folk to give ear to whatever is comforting; it is their settled faith that whatever is desirable will come to pass. A caressing confidence—but one, unfortunately, that is not borne out by human experience. The fact is that some of the things that men and women have desired most ardently for thousands of years are not nearer realization today than they were in the time of Rameses, and that there is not the slightest reason for believing that they will lose their coyness on any near tomorrow. Plans for hurrying them on have been tried since the beginning; plans for forcing them overnight are in copious and antagonistic operation today; and yet they continue to hold off and elude us, and the chances are that they will keep on holding off and eluding us until the angels get tired of the show, and the whole earth is set off like a gigantic bomb, or drowned, like a sick cat, between two buckets.

Turn, for example, to the sex problem. There is no half-baked ecclesiastic, bawling in his galvanized-iron temple on a suburban lot, who doesn’t know precisely how it ought to be dealt with. There is no fantoddish old suffragette, sworn to get her revenge on man, who hasn’t a sovereign remedy for it. There is not a shyster of a district attorney, ambitious for higher office, who doesn’t offer to dispose of it in a few weeks, given only enough help from the city editors. And yet, by the same token, there is not a man who has honestly studied it and pondered it, bringing sound information to the business, and understanding of its inner difficulties and a clean and analytical mind, who doesn’t believe and hasn’t stated publicly that it is intrinsically and eternally insoluble. For example, Havelock Ellis. His remedy is simply a denial of all remedies. He admits that the disease is bad, but he shows that the medicine is infinitely worse, and so he proposes going back to the plain disease, and advocates bearing it with philosophy, as we bear colds in the head, marriage, the noises of the city, bad cooking and the certainty of death. Man is inherently vile—but he is never so vile as when he is trying to disguise and deny his vileness. No prostitute was ever so costly to a community as a prowling and obscene vice crusader, or as the dubious legislator or prosecuting officer who jumps at such swine pipe.

Leave a Reply